One of the most common negative consequences of suffering from stress for a long period of time is increased anxiety. But also short but intense bouts of stress can increase anxiety, and even provoke panic attacks, scientists have found.

Stress versus anxiety

Stress and anxiety are closely related, but are not the same. Stress is typically caused by an external trigger. The trigger can be short-term, such as a work deadline or a fight with a loved one, or long-term, such as being unable to work, discrimination, or chronic illness. People under stress experience mental and physical symptoms, such as irritability, anger, fatigue, muscle pain, digestive troubles, and difficulty sleeping.

Anxiety, on the other hand, is defined by persistent, excessive worries that don’t go away even in the absence of a stressor. Anxiety leads to a nearly identical set of symptoms as stress: insomnia, difficulty concentrating, fatigue, muscle tension, and irritability.

Furthermore, while stress is the body's reaction to a threat, anxiety can be considered the brain's reaction to the stress. In other words, stress can cause anxiety.

Chronic stress can enhance anxiety

Biological studies in mice have found that being stressed out for a long period of time increase anxiety. It seems that at least one of the culprits is the stress hormone cortisol.

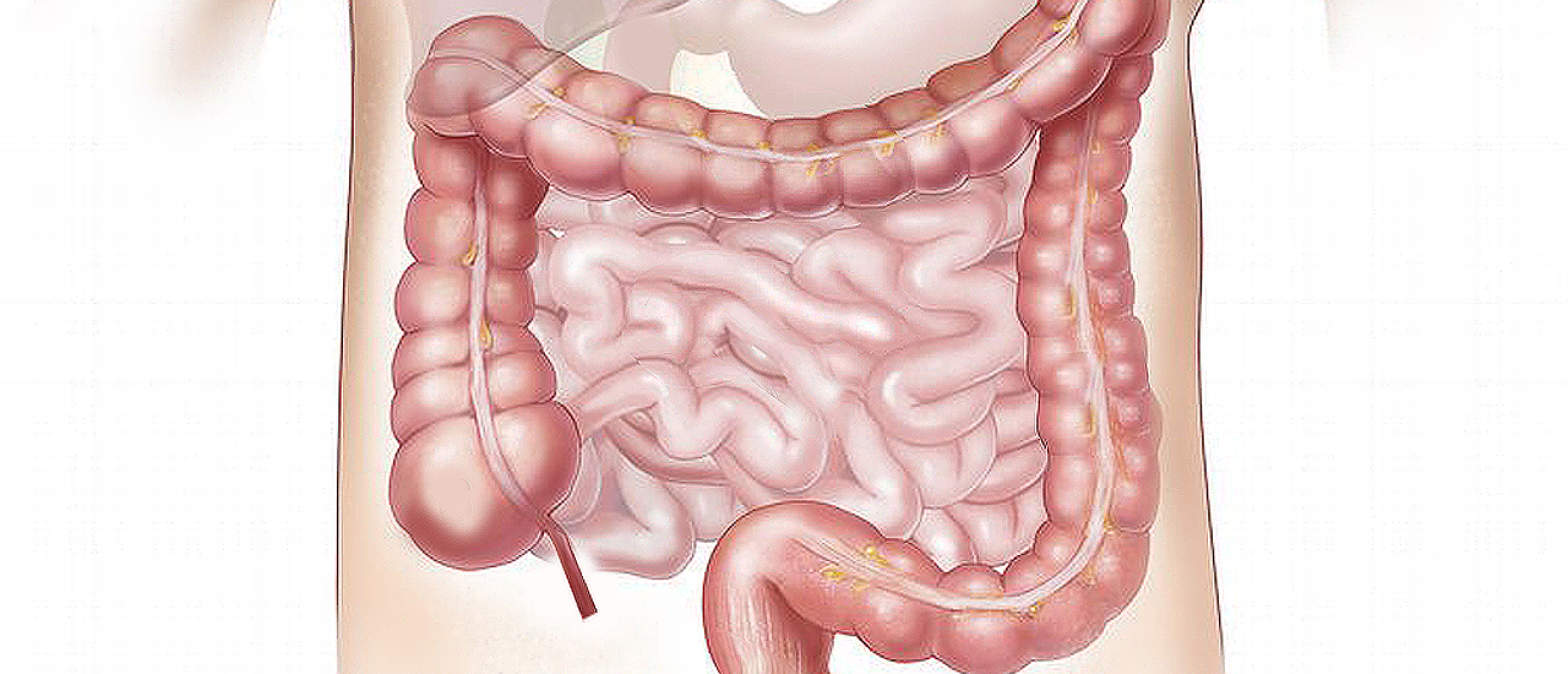

Cortisol is synthesized by the adrenal glands, located on top of the kidneys. Its release is stimulated by the hypothalamus in the brain and the pituitary gland at the base of the brain.

Cortisol has many positive effects to deal with problems that cause stress. It liberates energy from the liver and redistributes energy to those organs that are active to fight off the stress. However, if cortisol levels remain high for a long period of time, i.e. when stress becomes chronic, cortisol does more harm than good. One of the effects of chronic stress and chronically high cortisol is increased anxiety.

To mimic chronic stress, researchers have spiked the drinking water of mice with corticosterone (the mouse equivalent of human cortisol) for 18 days. Following this, the mice were very reluctant to explore brightly lit open spaces, which is a sign of anxiety. Mice that received corticosterone for only one day were happy to go into the open, and potentially dangerous, space.

Also, the mice that drank the water spiked with corticosterone for 18 days did not react so much to a noxious tone. It seemed therefore that the stress response, that would normally occur, was blunted. This was probably due to downregulation of the hypothalamus and other brain regions by corticosterone. This reduces the acute stress response and increases symptoms of depression.

How would these results translate to humans? This is not so easy to say. Obviously, mice are not humans, so stress may not enhance anxiety in humans. Also, corticosterone administration over a long period of time may resemble chronic stress, but is not the same. During chronic stress, many hormones and brain regions are involved, and corticosterone is only one of them, however important.

Intense acute stress in humans who are anxiety-sensitive

Let’s therefore have a look at a human study on the effects of stress on anxiety. Researchers have followed over 1,000 young men over the course of five weeks, and who were first year students with the United States Air Force Academy (USAFA). The initial five weeks of training (the basic cadet training) is a typical stressful time. This period consists of highly regimented training, and is accompanied by quite extreme psychosocial and physical stressors.

Psychosocial stressors include isolation from friends and family, and constant monitoring and evaluation of behavior and performance. Physical stressors are things like intense exercise and sleep deprivation.

In general, the basic cadet training is designed to continuously expose cadets to a variety of unpredictable and uncontrollable physical and mental stressors. Cadets are not given schedules and have no access to clocks or watches. They cannot predict whether their next activity will be an academic evaluation, a military exercise, or a 5-mile run. New stressors are continually introduced to ensure that each cadet is finding himself under high pressure and stress.

While you may think that these stressful conditions augment anxiety for all the new cadets, this turned out not to be the case. Whether anxiety increased depended on anxiety sensitivity of each individual cadet.

Anxiety sensitivity refers to the extent that you take symptoms of anxiety such as nausea and palpitations as dangerous. For example, you might be trembling and you immediately think you have a neurological disorder. Or you might feel light in the head, and you are convinced that you have a brain tumor.

Among the cadets, 20% of those with strong anxiety sensitivity showed enhanced anxiety after the five weeks training period, which manifested itself as panic attacks. Only 6% of the cadets with lower anxiety sensitivity had panic attacks.

Thus, periods of intense stress over a few weeks period can intensify anxiety, but only if you interpret symptoms of anxiety erroneously as harmful. Anxiety sensitivity has been linked to certain personality profiles, positively with neuroticism (negative emotionality) and negatively with extraversion. Thus, the stronger the personality trait of negative emotionality, and the weaker the extraversion trait, the higher the probability that someone will be highly anxiety sensitive.

Stress sensitivity is partially determined by personality traits. What might be stressful for one person might not be so for another. This is another link between stress anxiety. But strongly linked as they may be, they also are subtly different. Now you know why.